Your cart is empty.

Visit the store to add items to your cart.

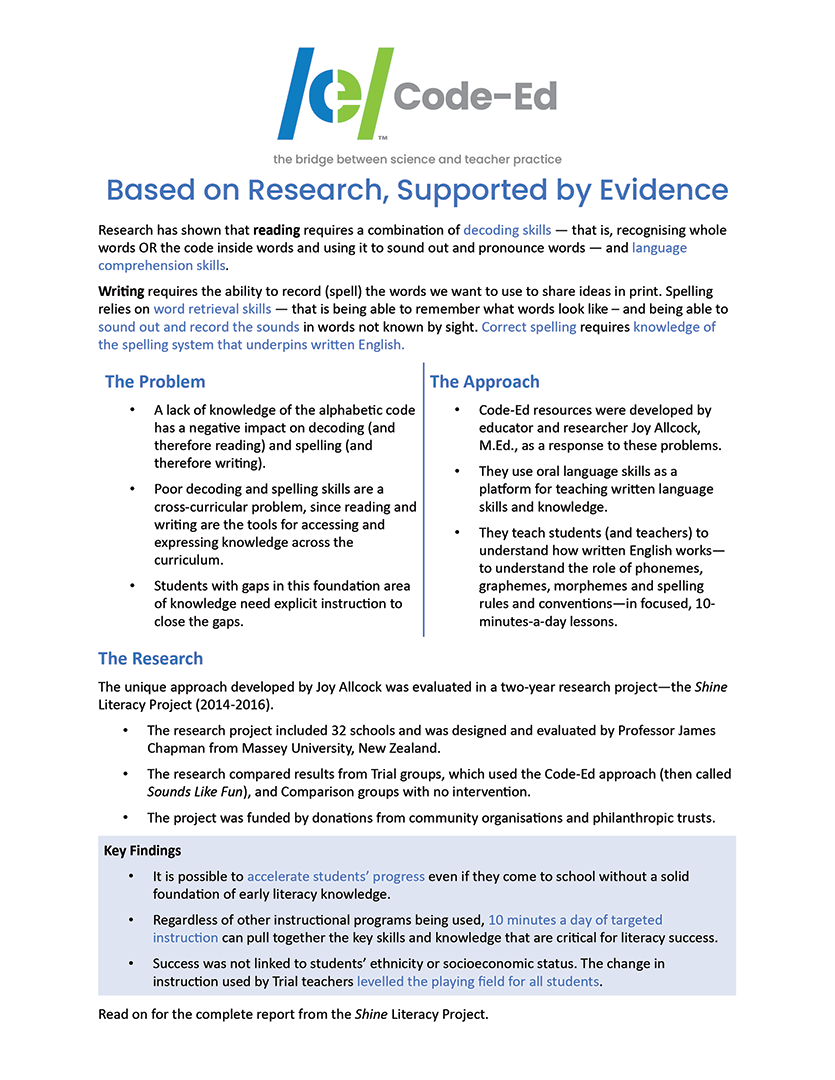

Research has shown that reading requires a combination of decoding skills — that is, recognising whole words OR the code inside words and using it to sound out and pronounce words — and language comprehension skills.

Writing requires the ability to record (spell) the words we want to use to share ideas in print. Spelling relies on word retrieval skills — that is being able to remember what words look like — and being able to sound out and record the sounds in words not known by sight. Correct spelling requires knowledge of the spelling system that underpins written English.

The unique approach developed by Joy Allcock was evaluated in a two-year research project—the Shine Literacy Project (2014-2016).

Code-Ed Research and Evidence

Find out more about the research behind Code-Ed!

Catch Up Your Code Research and Evidence

Discover the research and evidence behind Catch Up Your Code

A professional development journey and its link to student success

Read about Joy Allcock's research in the New Zealand Education Gazette